LAND AREA:

FORESTED

AREA:

FOREST

TYPE:

FOREST

OWNERSHIP:

PROTECTED

AREAS:

VPA STATUS:

65.3 million hectares¹

29 million hectares²

44% of total land area²

11.0% primary²

86% naturally regenerated²

>99% state owned³

<1% designated for local communities³

4.8 million hectares⁴

15% of forests found in Protected Areas²

No VPA currently⁵

Preparing negotiations

ECONOMIC VALUE OF FOREST SECTOR:

USD 254.4 million in 2011⁶

0.5% of GDP in 2011⁶

11th largest global timber exporter in 2014 among ITTO members⁷

ANNUAL DEFORESTATION RATE:

340 thousand hectares of tree cover loss in 2017⁶

Average of 315 thousand hectares per year 2013 – 2017⁶

Globally 3rd largest net loss of forest area 2010-2015⁸

CERTIFIED FORESTS:

FSC certification:0 hectares (2018)⁹

PEFC certification:0 hectares (2017)¹⁰

National certification: 0 hectares (2014)²

CHAIN OF CUSTODY CERTIFICATION:

FSC certification: 1 CoC certificate (2018)⁹

PEFC certification: 0 (2017)¹⁰

MAIN TIMBER SPECIES IN TRADE:

Native species: Burma padauk (Pterocarpus macrocarpus), teak (Tectona grandis), terminalia (Terminalis tomentosa), Burmese ironwood (Xylia dolabriformis), daeng (X. kerri)¹¹

Plantation species: candahar (Gmelina arborea), rubberwood (Hevea brasiliensis)¹¹

CITES-LISTED TIMBER SPECIES:

29 species: Aquilaria malaccensis, Dalbergia assamica, D. burmanica, D. cana, D. candenatensis, D. cultrata, D. fusca, D. kingiana, D. lacei, D. lanceolaria, D. millettii, D. obtusifolia, D. oliveri, D. ovata, D. parviflora, D. penguensis, D. pinnata, D. prainii, D. pseudo-ovata, D. reniformis, D. rimosa, D. sericea, D. sissoo, D. spinosa, D. stipulacea, D. velutina, Diospyros ferrea, Taxus wallichiana (all Appendix II), Tetracentron sinense (Appendix III)¹²

RANKINGS IN GLOBAL FREEDOM AND STABILITY INDICES:

Rule of law index¹³

4th quarter

100/113 in 2017

Corruption perception index¹⁴

3rd quarter (score: 30)

130/180 in 2017

Fragile states index¹⁵

4th quarter

22/178 in 2018

(Inverse scoring system)

Freedom in the world index¹⁶

4th quarter

61/83 in 2018

LEGAL TRADE FLOWS

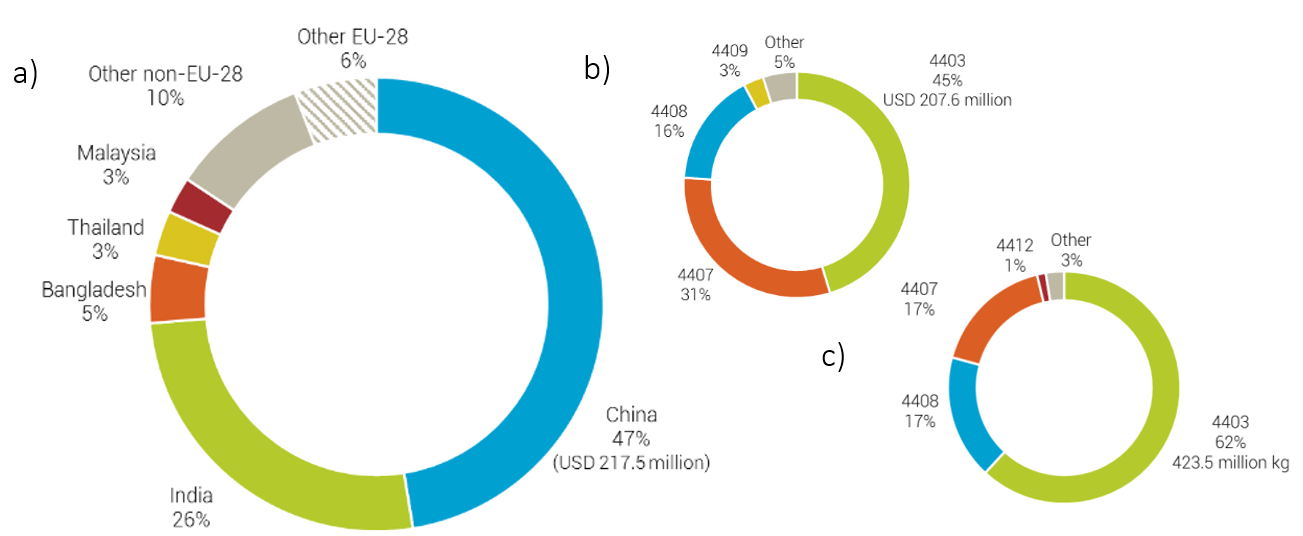

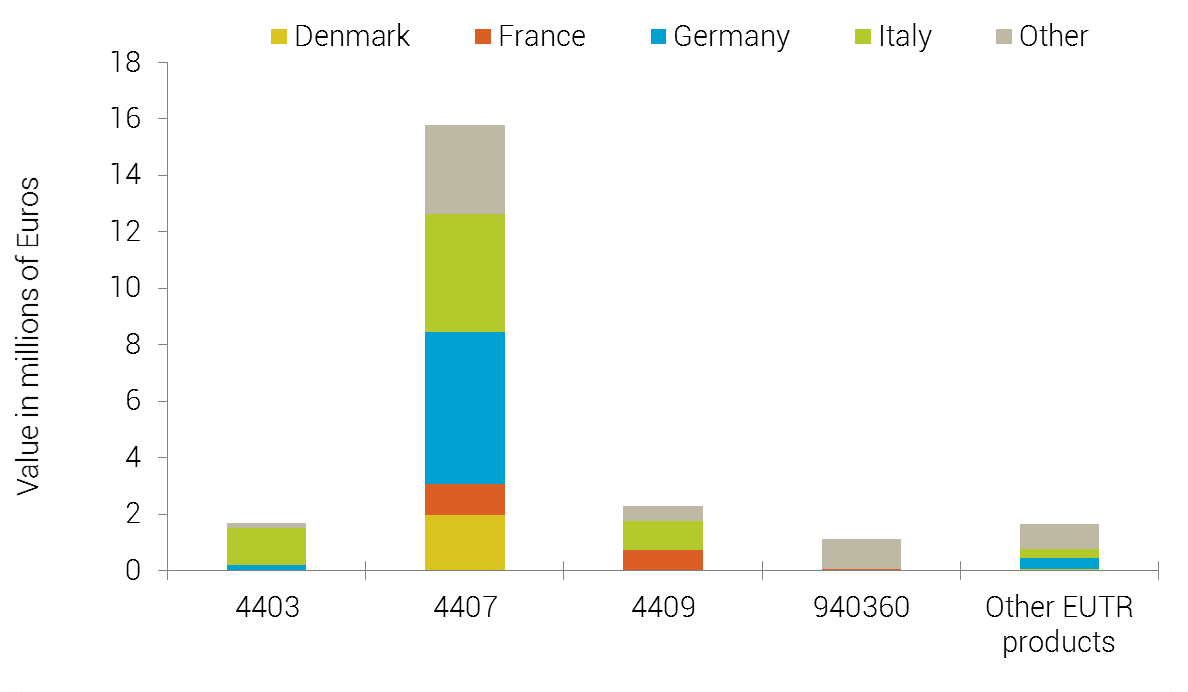

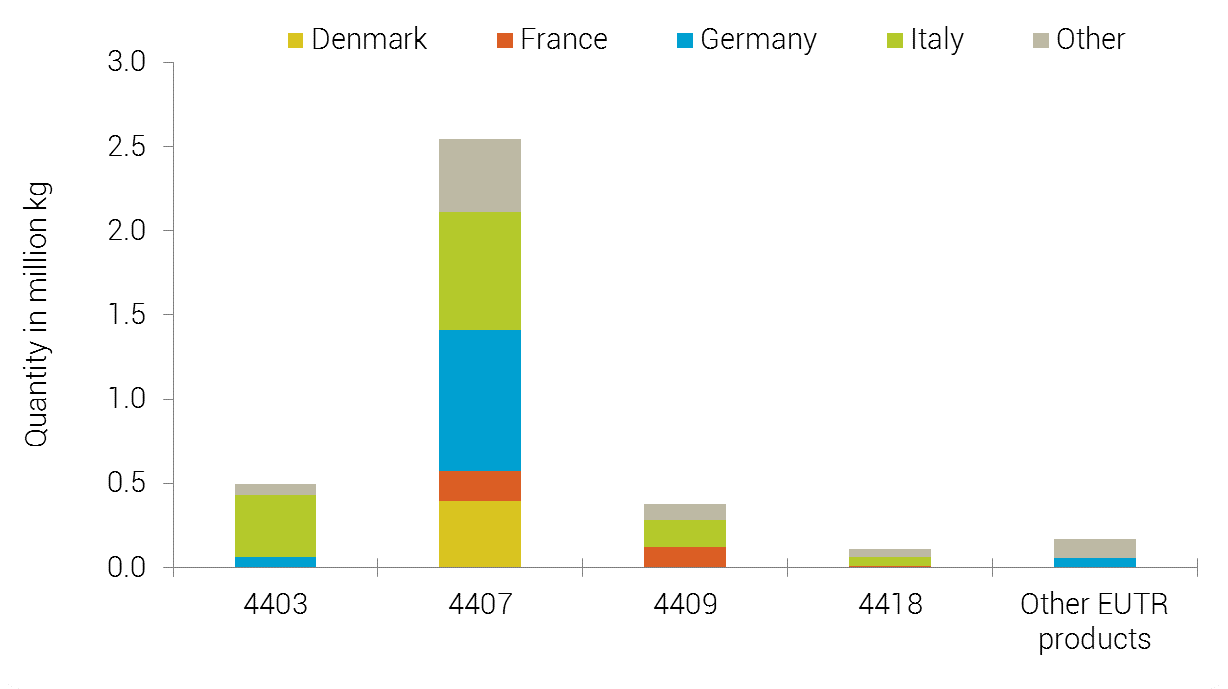

In 2015, Myanmar’s export of EUTR-regulated products totalled 684.2 million kg, of which 0.63% was exported to the EU-28. Exports of EUTR products mainly consisted of rough wood (HS4403*) by both weight and value (Figures 1b and 1c); Myanmar imported very little timber and consumed over half of its roundwood production (Table 1). China and India were the main importers of Myanmar’s EUTR-regulated products in 2015 (Figure 1a); the EU imported less than 1% of all EUTR-regulated products exported from Myanmar by weight. However, due to the relatively high value of sawn wood, the EU imported 4% of the value of Myanmar’s EUTR product exports in 2015 (approx. USD 19.8 million of a total value of approx. USD 481.2 million). The majority of EUTR-regulated products imported into the EU from Myanmar in 2015 were imported by Denmark, France, Germany, and Italy (Figures 2 and 3). For further information, see Annex 1.

Figure 1: a) Main global markets for EUTR products from Myanmar in 2015 in USD; b) main EUTR products by HS code exported from Myanmar by value in USD in 2015; and c) main EUTR products by HS code exported from Myanmar by weight (kg) in 2015. Produced using trading partner reported data from UNCOMTRADE (Myanmar reported export data was not available at the time of writing)18.

Table 1: Production and trade flows of main timber products in Myanmar in 201519.

| Production (x 1000 m³) |

Imports (x 1000 m³) |

Domestic consumption (x 1000 m³) |

Exports (x 1000 m³) |

|

| Logs (industrial roundwood) | 5 954 000 | 0 | 3 670 000 | 2 285 000 |

| Sawnwood | 1 610 000 | 0 | 1 396 000 | 214 000 |

| Veneer | 44 000 | 0 | 8 000 | 37 000 |

| Plywood | 116 000 | 5 000 | 108 000 | 13 000 |

Figure 2: Value of EU imports of EUTR products from Myanmar to the EU in 2015 by HS code. Produced using data from EUROSTAT17.

Figure 3: Quantity of EU imports of EUTR products from Myanmar to the EU in 2015 by HS code. Produced using data from EUROSTAT17.

*Key to HS codes: 4403 = rough wood; 4407 = sawn wood; 4408 = veneer sheets; 4409 = continuously shaped wood; 4412 = plywood and veneered panels; 4418: joinery and carpentry wood; 940360 = other wooden furniture

KEY RISKS FOR ILLEGALITY

COMPLIANCE WITH LEGISLATION:

Potential issues with compliance with the Myanmar Selection System (Myanmar’s forest management system) by the Myanmar Timber Enterprise20.

BRIBERY INCIDENCE:

42.9% of firms experiencing at least one bribe payment request in 201421

Based on data collected on behalf of the World Bank across a range of sectors

ILLEGAL HARVESTING OF SPECIFIC TREE SPECIES:

Burmese teak (Tectona grandis) and other hardwoods22

PREVALENCE OF ILLEGAL HARVESTING OF TIMBER:

Reportedly widespread22,23,24, especially along inland national borders20,25,26

RESTRICTIONS ON TIMBER TRADE

Myanmar banned exports of raw logs (HS4403) from 1 April 201422; there is currently no indication of when this ban will be lifted43.

All logging activity was temporarily banned in 2016, with the ban lifted 1st April 201727.

Logging of teak in the Bago-Yoma Range was banned for 10 years from 201628.

Export of products based on confiscated timber are prohibited from April 201729.

No EU30 or UN31 sanctions on timber exports or imports.

COMPLEXITY OF THE SUPPLY CHAIN

Forests are largely owned and managed by the Forest Department, an agency under the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation (MONREC); the Forest Department sets the annual allowable cut (AAC) of timber for the country28. The Myanmar Timber Enterprise (MTE), also under MONREC, is authorised to log forests by the Forestry Department; MTE then transports logs to depots and sells to private companies, which can only purchase logs from the State28. All exports are supposed to be approved by the MTE, and exported through ports in Yangon20. However, cross-border trade in illegally harvested timber to neighbouring countries such as China, India and Thailand is significant22,26. The Myanmar Timber Merchants Association (MTMA), a state-backed private business, is the main exporter20. The process applies to managed natural forests and conversion forests28. Currently, most timber is harvested from natural forests32. Timber from different sources is usually combined for export20.

Illegal trade

Logging in Myanmar has historically suffered issues of corruption, weak forest governance and law enforcement26,33,34 and a pressure to generate revenue leading to sub-contracting of logging and compromised traceability26,35. This has led to systematic over-exploitation26,36 as well as issues such as illegal harvesting in conflict areas (most notably in Kachin state)33, irregularities in the conversion of gazetted forest37, mixing of unaccounted and accounted timber26,35, and illicit cross-border trade to China and elsewhere26,22. Logging quotas have historically often been set in excess of the annual allowable cut, resulting in over-harvesting23, and a 2014 report by Forest Trends found that corruption was considered “normal” business practice among interviewees25.

More recently, as part of its transition towards a democratic system, Myanmar has made efforts to address issues with its forest management and timber trade, with a ban placed on the export of raw logs and a specialised Forestry Police established in 201422. Further information on recent government efforts to reform the sector are provided in the next section. However, illegal logging and export of timber is still documented as an issue in the country22,36,35. In a 2017 risk assessment of timber legality in Myanmar, NEPCon identified a wide range of key risks including: illegal assignment of harvest permits; illegal conversion of forest areas to agriculture; avoidance of paying royalties, harvesting fees and taxes; violation of forest management laws, regulations and rules; conflicts over land resources and involving indigenous peoples; and the falsification of documents35. The majority of illegal timber has been exported via overland borders with China, India and Thailand22,26. The risk of timber illegally harvested in Myanmar being re-exported to the EU or other markets from its neighbouring countries is therefore high. Shipments are also smuggled out via the main port in Yangon, such as the 571 tonne shipment seized there in January 201738. The value of illegal timber seizures has also reportedly grown over the past five years, with a reported rise from 105 600 EUR in 2013 to 9.5 million EUR in 2016, according to media reports referencing Myanmar government data17. This shows increased attention on law enforcement by the Government of Myanmar.

Verifying the legality of timber from land conversion areas is challenging, due to issues such as the lack of legal documentation for the process of de-gazetting Permanent Forest Estates37. It is also not possible to verify the legality of timber sourced from non-state-controlled sources in contested areas; this timber is often illegally exported across land borders and may eventually reach EU markets26,28. The “Green Folder”, produced by Myanmar Forest Products Merchants’ Federation (MFPMF) and used to demonstrate that timber purchases are compliant with Myanmar forest law, was ruled to be insufficient to prove a negligible risk of illegality by the Swedish courts in November 2016, as the documents do not provide, inter alia, sufficient information on the origin of logs, logging companies involved and compliance with Myanmar’s forest legislation – all necessary to determine whether any product is legal39,40,41.

The import of Burmese teak to the EU is a particular source of concern. A 2016 EIA investigation found that MTE prevents companies from acquiring or verifying necessary documentation, with companies therefore unable to comply with EUTR due diligence and to adequately mitigate the risks of importing timber from Myanmar36. In October 2016, EIA submitted “substantiated concerns” to Competent Authorities in Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark and Germany for violations of EUTR involving nine companies importing Burmese teak from Myanmar36. A number of European companies have been taken to court over breaches of EUTR resulting from trade in timber imported from Myanmar42,43,44.

The Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation (MONREC) has acknowledged the concerns of importing countries and stated that they are committed to streamlining their system to enable EUTR due diligence to be met45. In June 2017, the EUTR/FLEGT Expert Group (consisting of the European Commission and EUTR Competent Authorities) concluded that assurances (such as those provided by Double Helix) that Competent Authorities have received regarding sourcing of timber from Myanmar are not supported by appropriate evidence covering the whole supply chain and therefore cannot demonstrate full compliance with EUTR46. This also applies to the “Form D” which was seen accompanying shipments46. This assessment was reconfirmed in November 2017 where it was concluded that “there is insufficient information for operators to demonstrate the actual origin of the timber which would enable them to carry out a full risk assessment or mitigation in the exercise of due diligence”47.

Forestry management and legislation

In light of these issues and recent substantiated concerns submitted regarding alleged insufficient due diligence processes by operators importing Myanmar timber products36, the government has enacted various measures to improve the status of timber harvesting in Myanmar, including various logging bans (see box above), ceasing the use of contractors to carry out logging, end to the ‘modified procedure’ [which was used in conflict areas] and reducing annual allowable cut levels to less than half of those in effect prior to the 2016 moratorium28,48. Export of products based on confiscated timber were prohibited from April 2017 and a new 10% export tax was imposed on wood log and wood cuttings from the same time29. MONREC has developed a new ‘Chain of Custody dossier’ to assist operators in their due diligence49. It contains copies of all relevant documents produced at each control point, from the Annual Allowable Cut declaration to the point of product export, facilitating traceability49. MONREC also confirmed that the export of conversion timber from land use change was prohibited in 201749.

The Myanmar Forest Certification Committee (MFCC) is also in the process of strengthening the existing Myanmar timber legality assurance system (MTLAS), with control procedures that will be subject to an independent monitoring process by third-party monitors32. This process is expected to address the findings of a gap analysis of the MTLAS which indicated that there are significant gaps, particularly as regards a) scope of legality in the forest, b) mechanisms for supply chain control, and c) independent assurance, oversight and monitoring50. The government has also stated that while it will be possible to provide documentation for stockpiled timber harvested in the 2015-2016 season, it may not be possible to do the same for older stockpiled logs28. In mid-2017, MTE announced that they had engaged private sector service providers to support MTE if they face insufficient capacity or facilities during the 2017-2018 logging season51. MTE reported in an International Tropical Timber Organisation newsletter that potential contractors are allocated contracts after submitting proposals to regional MTE officials, who then consult with MTE headquarters51. EIA expressed concern that the allocation of harvesting rights during the logging season is at high risk of corruption and bribery36.

In September 2017, the EUTR/FLEGT Expert Group concluded that the lack of sufficient information on harvesting volumes authorised for cutting, sufficient data for clear attribution of origin within the country to exclude conflict timber, and the high risk of mixing legally harvested with illegally harvested logs in the saw mills often owned by MTE, combined with the high corruption index, make it impossible for any verification service to mitigate risk to a negligible level that timber from Myanmar was illegally harvested 52. The Expert Group reiterated this finding in November 2017, in particular with regard to the information provided to determine the origin of timber47.

The Singapore based company DoubleHelix is establishing DNA reference data for populations of Myanmar teak, with a DNA-based verification system expected to be in place by 201853. In 2018, MONREC reported that it has given the MFCC a mandate to create a third party verification system, with initial selection of 3 national and one international body49.

| RELEVANT LEGISLATION AND POLICY[1] | ||

| For further details on Myanmar’s legislation relevant to EUTR, see the Myanmar country page on FAOLEX and NEPCon (2017) ‘Timber legality risk assessment’. | ||

| Forest Law, 1992: Some amendments to this law are currently being considered,54,43.

Myanmar Forest Policy, 1995 Forest Rules. 1995 Community Forestry Instructions, 1995: 2016 amendments are pending, awaiting the amendments to the Forest Law31 Protection of wildlife and wild plants and conservation of natural areas law, 1994 Environmental Conservation Law, 2012: A new policy is currently under development31 National Code of Forest Harvesting, 2000 Myanmar Timber Enterprise Extraction Manual, 1936 Natural Areas Law, 1994 |

The State Timber Board Act, 1950

Fallow Land, Vacant Land and Wild Land Law, 2012: for further details see Annex 6. Occupational Health and Safety Act Workmen’s Compensation Act, 1923 (amended 2005) Myanmar Customs Act, 1992 Control of Export and Import Acts, 1992 Myanmar Companies Act. 1914 Myanmar Citizens Investment Law, 1994 Foreign Investment Law, 2012 Foreign Investment Rule, 2013 The Commercial Tax Law, 1990 |

|

| LEGALLY REQUIRED DOCUMENTS[2] | ||

| See NEPCon (2017) ‘Timber legality risk assessment’ for a further list of legally required documents. | ||

| Permit to enter the forest and harvest timber approved by Forest Department

Schedule (II) of area and number of trees to be worked Document detailing return of coupes after logging Form for inspecting stumps in logged coupes Report on the inspection of harvest by legal harvesters during a specified period Registration for hammers MTE hammer marking and timber extraction control form Harvesting plan Marking book with standing tree number and map Records of joint measurement by the Forest Department and MTE Buyer’s receipt letter of logs in the log yard Logs delivery order: transfer of property from MTE to buyer Log specification issued by MTE Sales contract between MTE and private factory Material transfer note to factory issued by MTE |

Mill licence

Cutting permit (in sawmill) Yield calculation lot by lot (sawmills)] Out-turn percentage (in sawmill) approved by Forest Department Out-turn percentage approved by Forest Department Packing list approved by Forest Department Inspection by Forest Department at sawmill Export licence Export declaration Bill of landing Packing list Certificate of origin Receipt from MTE export for commercial tax payment Commercial invoice Documents not relevant since the government stopped the use of contractors in 2016: Legal certificate of incorporation of harvesting company (contractor), Official permission to work in timber extraction (contractor), Harvesting contract with MTE, Letter for harvesting company (contractor) to transport logs from forest |

|

[1] The following list may not be exhaustive and is intended as a guide only on relevant legislation.

[2] The following list may not be exhaustive and is intended as a guide only on required documents.

References

- FAO. FAO Country Profiles: Myanmar. (2018). Available at: http://www.fao.org/countryprofiles/index/en/?iso3=MMR. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015. Desk reference. (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2015).

- Rights and Resources Initiative. Tenure data tool. (2018). Available at: https://rightsandresources.org/en/work-impact/tenure-data-tool/#.WjjlOVVl9ph. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- UNEP-WCMC. Protected Area Profile for Myanmar from the World Database of Protected Areas. (2018). Available at: https://www.protectedplanet.net/country/MM. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- EU FLEGT Facility. VPA countries. (2018). Available at: http://www.euflegt.efi.int/vpa-countries. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- Global Forest Watch. Myanmar Country Profile. (2018). Available at: http://www.globalforestwatch.org/country/MMR. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- International Tropical Timber Organization. Annual Review Statistics Database. (2018). Available at: http://www.itto.int/annual_review_output/. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015: How are the world’s forests changing? (Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, 2016).

- FSC. Facts and figures August 2018. (Forest Stewardship Council, 2018).

- PEFC. PEFC Global Certification: Forest Management & Chain of Custody. (2017). Available at: https://www.pefc.org/resources/webinar/747-pefc-global-certification-forest-management-chain-of-custody. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- European Timber Trade Federation. Myanmar Industry Profile. Gateway to International Timber Trade (2018). Available at: http://www.timbertradeportal.com/countries/myanmar/. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- UNEP-WCMC. The Species+ Website. Nairobi, Kenya. Compiled by UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge, UK. (2018). Available at: https://speciesplus.net/. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- World Justice Project. Rule of Law Index 2017-2018. (2018). Available at: http://data.worldjusticeproject.org/. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- Transparency International. Corruption Perceptions Index 2017. (2018). Available at: https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2017. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- Fund for Peace. Fragile States Index 2018. (2018). Available at: http://fundforpeace.org/fsi/. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- Freedom House. Freedom in the World. (2018). Available at: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world-2018-table-country-scores. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- Win, S. P. Value of seized illegal timber rising yearly. Myanmar Times (2017).

- United Nations Statistics Division. UNCOMTRADE database. (2017). Available at: https://comtrade.un.org/data/.

- European Timber Trade Federation. Republic of the Congo Industry Profile (Timber). (2016). Available at: http://www.timbertradeportal.com/countries/congo/.

- Woods, K. Timber Trade Flows and Actors in Myanmar: The Political Economy of Myanmar’s Timber Trade. (Forest Trends, 2013).

- The World Bank. Bribery incidence (% of firms experiencing at least one bribe payment request). (2017). Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IC.FRM.BRIB.ZS.

- UNODC. Criminal justice response to wildlife and forest crime in Myanmar. (UNODC, 2015).

- Woods, K. & Canby, K. Baseline study, 4: Myanmar: Overview of forest law enforcement, governance and trade. (Forest Trends for FLEGT Asia Regional Programme, 2011).

- The Irrawaddy. Forest department investigates siezable seizures of smuggled timber. (2017). Available at: https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/forest-department-investigates-sizeable-seizures-smuggled-timber.html. (Accessed: 3rd May 2017)

- Forest Trends. Analysis of the China-Myanmar Timber Trade. (Forest Trends, 2014).

- EIA. Organised Chaos: The illicit overland timber trade between Myanmar and China. (EIA, 2015).

- Forest Trends. European, US, and Australian markets are still importing logs from countries with full or Partial log export bans. Forest trends information brief (Forest Trends, 2017).

- Leal, I. Iona Leal, EU FLEGT Facility pers. comm. to UNEP-WCMC 23 March 2017. (2017).

- Pyidaungsu Hluttaw. Union Tax Law 2017 (Pyidaungsu Hluttaw Law No.4 ). (2017).

- European Commission. European Union Restrictive measures (sanctions) in force. (European Commission, 2017).

- United Nations Security Council. Consolidated United Nations Security Council Sanctions List 27 November 2017. (United Nations Security Council, 2017).

- MFCC. Myanmar Timber Legality Assurance System (TLAS). (Myanmar, Working Group of the Timber Certification Committee of Myanmar, 2013).

- NEPcon. Myanmar forest sector legality analysis. (2013).

- WWF. Ecosystems in the Greater Mekong Past trends, current status, possible futures. (2013).

- NEPCon. Timber legality risk assessment Myanmar. Version 1.1. (2017). Available at: https://www.nepcon.org/sites/default/files/library/2017-06/NEPCon-TIMBER-Myanmar-Risk-Assessment-EN-V1.pdf.

- EIA. Overdue diligence: Teak exports from Myanmar in breach of European Union rules. (EIA, 2016).

- Woods, K. Commercial Agriculture Expansion in Myanmar: Links to deforestation, conversion timber, and land conflicts. (Forest Trends, 2015).

- The Myanmar Times. 571 tonnes of illegal tumber seized in three separate raids at Yangon port. (2017). Available at: https://www.illegal-logging.info/content/571-tonnes-illegal-timber-seized-three-separate-raids-yangon-port. (Accessed: 22nd February 2017)

- Forest Trends. Press release: Swedish court rules Myanmar timber documentation inadequate for EU importers. 2 (2016). Available at: https://www.forest-trends.org/wp-content/uploads/imported/swedish-court-myanmar-timber-pr_final-pdf.pdf.

- ClientEarth. Swedish administrative court confirms EUTR fine on retailer Dollarstore. (2018). Available at: https://www.documents.clientearth.org/library/download-info/swedish-administrative-court-confirms-eutr-fine-on-retailer-dollarstore/.

- Skogsstyrelsen. Pressmeddelande: Dålig koll på träslag i produkter gav vite på 800 000 [Press release: Bad list of wood products in the product gave rise to 800,000]. Available at: https://www.skogsstyrelsen.se/nyhetslista/dalig-koll-pa-traslag-i-produkter-gav-vite-pa-800-000/. (Accessed: 10th July 2018)

- EIA. Sweden prosecutes Myanmar teak trader. Eia (2016).

- Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority. Preventive measure issued against two Dutch companies for breaching the EU timber regulation. Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority (2017).

- Danish Environmental Protection Agency. Wooden importer reported for imports of teakwood from Myanmar. Danish Environmental Protection Agency (2017).

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation. Statement of Progress in Timber Legality Assurance in Myanmar. (The Republic of the Union of Myanmar, 2017).

- European Commission. Minutes of the FLEGT/EUTR Expert Group meeting. 16 June 2017. (2017).

- European Commission. Summary record of the FLEGT/EUTR Expert Group meeting. 23 November 2017. (2017).

- European Timber Trade Federation. ETTF News: EU and Myanmar take proactive steps on timber legality assurance. Myanmar special edition. June 2017. (2017). Available at: http://www.aeim.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/ETTF-Newsletter-Myanmar-Special-Edition-June-2017.pdf.

- MONREC. Presentation: The CoC dossier – Myanmar timber Chain of Custody process, documents and actors. FLEGT/EUTR expert group meeting, Brussels, 19 June 2018 Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regexpert/index.cfm?do=groupDetail.groupMeetingDoc&docid=14937.

- MFCC. Myanmar Timber Legality Assurance System (MTLAS) gap analysis project final report. (FAO-EU FLEGT Programme, 2017).

- ITTO. Tropical timber market report. Volume 21 Number 14, 16th-31st July 2017. (ITTO, 2017).

- European Commission. Summary record of the FLEGT/EUTR Expert Group meeting. 20 September 2017. (European Commission, 2017).

- DoubleHelix. Securing Myanmar teak supply chains with DNA. (2017). Available at: http://www.doublehelixtracking.com/news/2017/4/18/securing-myanmar-teak-supply-chains-with-dna. (Accessed: 3rd May 2017)

- ITTO. Tropical Timber Market Report. ITTO Mark. Inf. Serv. 21, 1–25 (2017).