PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA*

Country overview to aid implementation of the EUTR

LAND AREA:

FORESTED

AREA:

FOREST

TYPE:

LAND

OWNERSHIP:

PROTECTED

AREAS:

VPA STATUS:

942 million hectares¹

208.3 million hectares²

22.1% of total land area²

5.6% primary²

56.5% naturally regenerated²

39% state owned³

61% owned by local communities³

144.6 million hectares⁴

13.5% of forests found in protected areas²

No VPA currently⁵

Bilateral Coordination Mechanism established in 2009⁶

ECONOMIC VALUE OF FOREST SECTOR:

USD 125 billion in 2011⁷

1.7% of the GDP in 2011⁷

7th highest exporter of EUTR products globally in 2016 by weight (kg)⁸

Highest exporter of EUTR products globally in 2016 by value (USD)⁸

ANNUAL DEFORESTATION RATE:

None⁹

0.8% gain of forest area annually 2010-2015

Globally top largest net gain of forest area 2010-2015⁹

CERTIFIED FORESTS:

FSC certification: 988 thousand hectares (2018)¹⁰

PEFC certification: 5.7 million (2017)¹¹

Domestic forest management certification: 0.7 million hectares (2014)²

CHAIN OF CUSTODY CERTIFICATION:

FSC certification: 6146 CoC certificates (2018)¹⁰

PEFC certification: 289 CoC certificates (2017)¹¹

MAIN TIMBER SPECIES IN TRADE:

Natural forests (pre-logging ban): Faber’s fir (Abies fabri), birch (Betula spp.), Chinese weeping cypress (Cupressus funebris), Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata), dragon spruce (Picea asperata), Sikang pine (Pinus densata), Chinese red pine (Pinus massoniana), Yunnan pine (Pinus yunnanensis), oak (Quercus spp.)¹²

Plantations: Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata), Chinese weeping cypress (Cupressus funebris), eucalyptus spp., dahurian larch (Larix gmelinii), American pitch pine (Pinus elliottii), Chinese red pine (Pinus massoniana), Chinese pine (Pinus tabulaeformis), poplar (Populus spp.), oak (Quercus spp.), black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia)¹²

CITES-LISTED TIMBER SPECIES:

46 species: Aquilaria grandiflora, A sinensis, A. yunnanensis, Dalbergia assamica, D. balansae, D. benthamii, D. burmanica D. candenatensis, D. cultrara, D. dyeriana, D. fusca, D. hainanensis, D. hancei, D. henryana, D. hupeana, D. jingxiensis, D. kingiana, D. millettii, D. mimosoides, D. obtusifolia, D. odorífera, D. peishaensis, D. pinnata, D. polyadelpha, D. rimosa, D. rubiginosa, D. sacerdotum, D. sericea, D. sissoo, D. stenophylla, D. stipulacea, D. tonkinensis, D. tsoi, D. volubilis, D. ximengensis, D. yunnanensis, Taxus chinensis, T. cuspidata, T. fuana, T. sumatrana, T. wallichiana (all Appendix II), Fraxinus mandshurica, Pinus koraiensis, Podocarpus neriifolius, Quercus mongolica and Tetracentron sinense (Appendix III)13

RANKINGS IN GLOBAL FREEDOM AND STABILITY INDICES:

Rule of law index¹⁴

3rd quarter

75/113 in 2017

Corruption perceptions index15

2nd quarter (score: 41)

77/180 in 2017

Fragile states index¹⁶

3rd quarter

89/178 in 2018

(Inverse scoring system)

Freedom in the world index¹⁷

4th quarter

73/83 in 2018

LEGAL TRADE FLOWS

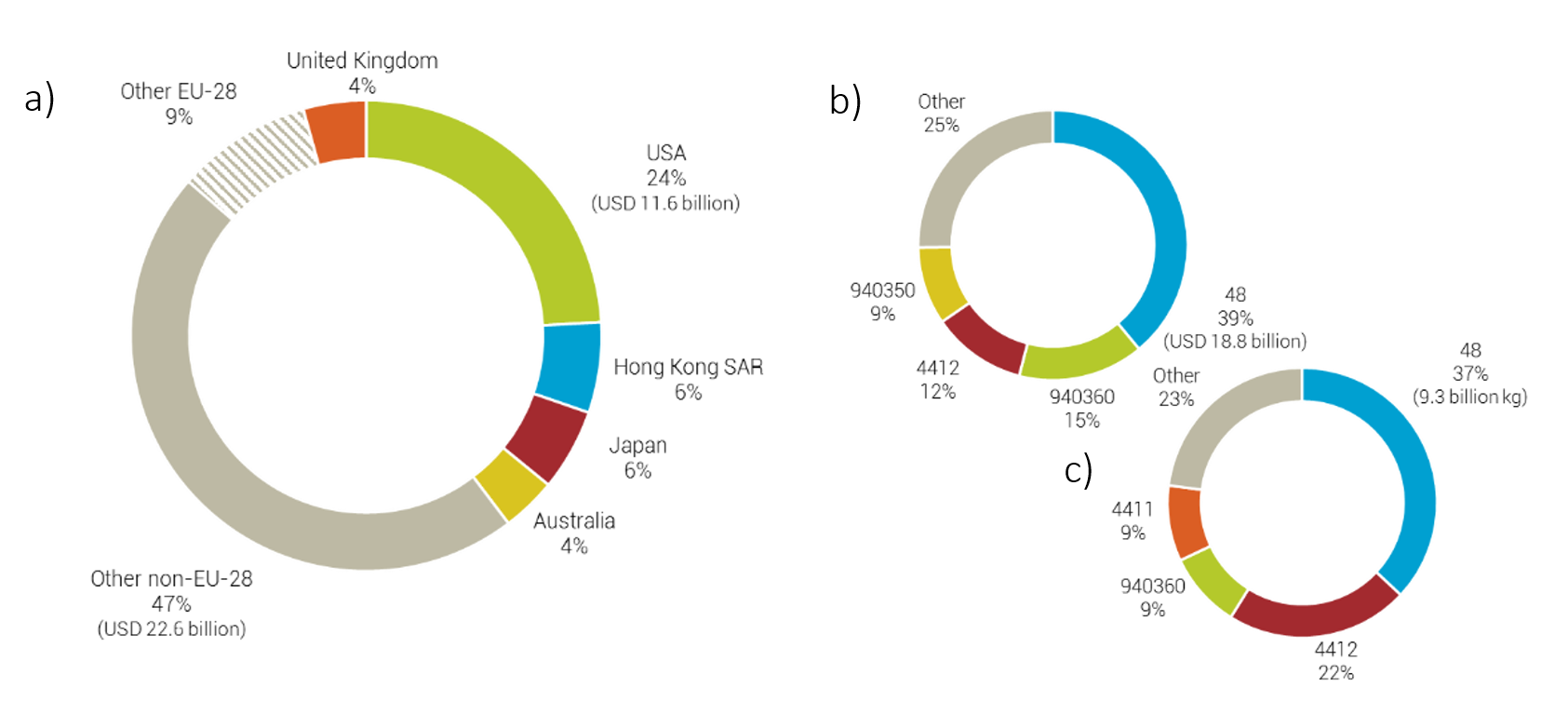

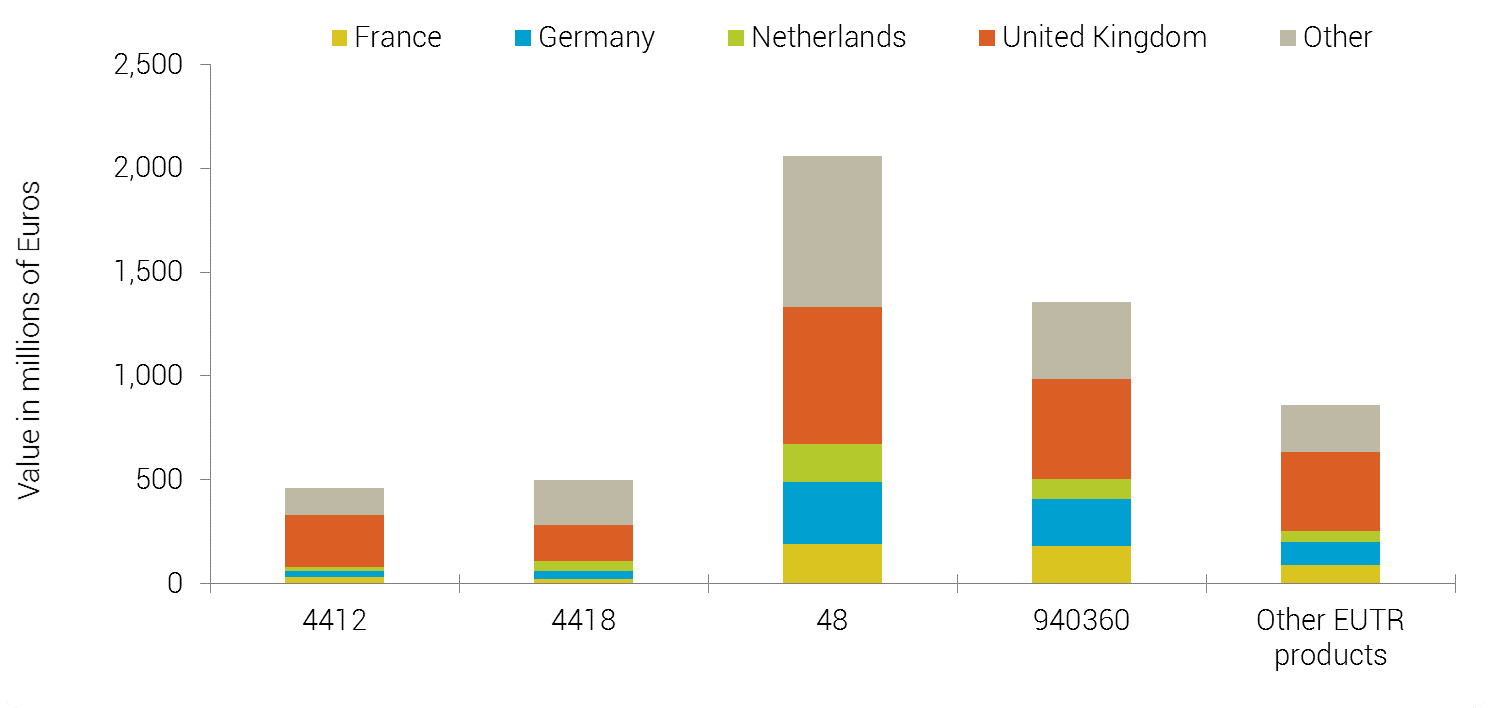

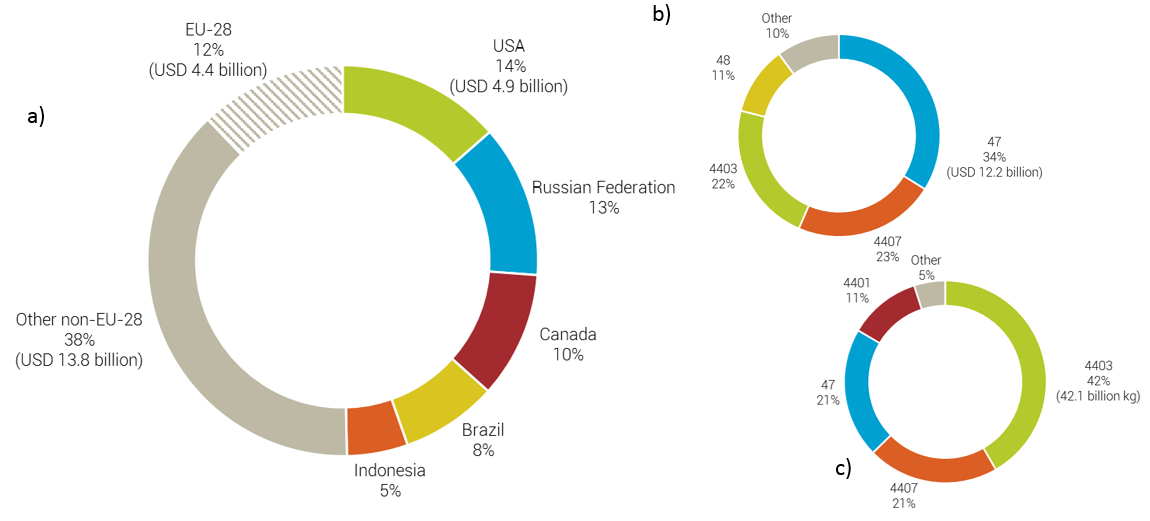

In 2015, China exported EUTR-regulated products to 212 different countries and territories, totalling 25.1 billion kg, of which 11.6% was exported to the EU-28. The United States was the largest single importer by value in 2015 (Figure 1a). Exports of EUTR-regulated products mainly consisted of paper products (HS48*) by both weight and value (Figures 1b and 1c). Exports were also dominated by fibreboard (HS4411), plywood (HS4412) and wooden furniture (HS940350 and HS940360). Domestic consumption exceeded production in 2014 for logs, sawnwood and veneer (Table 1), reflecting China’s role as a main producer of finished timber products. The majority of EUTR-regulated products imported into the EU from China in 2015 were imported by France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1: a) Main global markets for EUTR products from China in 2015 in USD; b) main EUTR products by HS code exported from China by value in USD in 2015; and c) main EUTR products by HS code exported from China by weight (kg) in 201519.

Table 1: Production and trade flows of main timber products in China in 201512.

| Production (x 1000 m³) |

Imports (x 1000 m³) |

Domestic consumption (x 1000 m³) |

Exports (x 1000 m³) |

|

| Logs (industrial roundwood) | 338 106 | 53 704 | 391 752 | 58 |

| Sawnwood | 68 410 | 27 365 | 95 352 | 423 |

| Veneer | 3033 | 1168 | 3887 | 315 |

| Plywood | 104 146 | 1086 | 93 887 | 11 345 |

Figure 2: Value of EU imports of EUTR products from China to the EU in 2015 by HS code. Produced using data from EUROSTAT18.

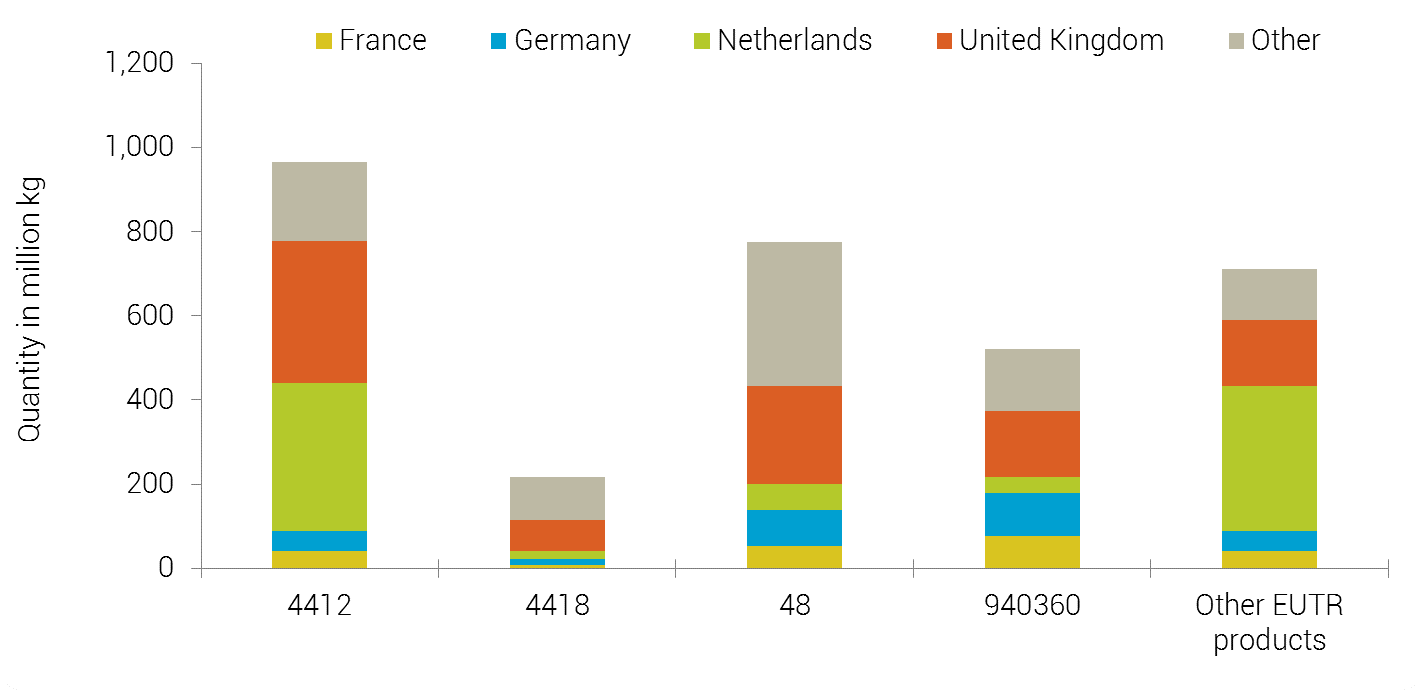

Figure 3: Quantity of EU imports of EUTR products from China to the EU in 2015 by HS code. Produced using data from EUROSTAT18.

Imports into China in 2016 of EUTR-regulated products totalled 36 billion USD, from 153 different countries and territories (Figure 4a). Imports of EUTR-regulated products mainly consisted of wood pulp (HS47), sawn wood (HS4407) and rough wood (HS4403) by both weight and value (Figures 4b and 4c).

Figure 4: a) Main global markets for EUTR products imported into China in 2016 in USD; b) main EUTR products by HS code imported into China by value in USD in 2016; and c) main EUTR products by HS code imported into China by weight (kg) in 201619.

*Key to HS codes: 4403 = rough wood; 4407 = sawn wood; 4411 = fibreboard; 4412 = plywood and veneered panels; 4418 = joinery and carpentry wood; 47 = wood pulp; 48 = paper and paper products; 940350 = wooden bedroom furniture; 940360 = other

KEY RISKS FOR ILLEGALITY

COMPLIANCE WITH LEGISLATION:

China does not currently have dedicated legislation in place prohibiting the import of illegal timber products20,21. The Regulation on the Implementation of the Forestry Law (2000) requires that timber cannot be sourced without harvesting permits (in the case of timber produced in China) or “other evidence of legal origin”, but it does not define what would constitute such evidence20.

BRIBERY INCIDENCE:

| 11.6% of firms experienced at least one bribe payment request in 201222. |

Based on data collected on behalf of the World Bank across a range of sectors.

ILLEGAL HARVESTING OF SPECIFIC TREE SPECIES:

Rosewood (especially Dalbergia spp.) is in high demand in China23 and one of the main groups of species reported in illegal timber trade in China24,25.

PREVALENCE OF ILLEGAL HARVESTING OF TIMBER:

| Domestic illegal logging was cited as an ongoing problem in China in 201226. |

China has been cited as probably the largest importer of illegal origin timber products globally27,28. An estimated 17% of imports into China of timber-based products had a high risk of illegality in 201323.

RESTRICTIONS ON TIMBER TRADE

|

China has a complete ban on commercial logging in all natural forests since 201729. |

No EU30 or UN31 sanctions on timber exports or imports.

COMPLEXITY OF THE SUPPLY CHAIN

China is a major importer of timber that is processed into timber and paper products in China for re-export, with timber from multiple sources often mixed during processing32.

Illegal trade

China is one of the world’s largest importers, consumer and exporter of wood-based products21, with almost half of the wood and wood fibre processed in the country sourced through imports33. The top 10 supplier countries of logs and sawn wood to China 2011-2015, based on Global Trade Atlas data, were reported to be the Russian Federation, Canada, New Zealand, the United States, Thailand, Papua New Guinea, Australia, Solomon Islands, Chile and Indonesia, with non-tropical timber producers dominating the list33.

Many Chinese forestry companies operate abroad, especially in the Russian Federation, Africa (including Gabon, Zambia, Equatorial Guinea, Liberia, Republic of the Congo and Cameroon), Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand, the Republic of Korea, Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela, Peru and Guyana34. While the proportion of imports of timber and paper products that are likely to be from illegal sources was believed to have declined between 2000 and 2013, the actual volume of such imports has increased, due to the overall growth in timber and paper imports over the period21. China has been cited as probably the largest importer of illegal origin timber products globally27,28. An estimated 33 million m3 of roundwood equivalent (RWE) of illegal timber and paper-sector products were imported into China in 2013, increasing from 17 million m3 RWE in 200021, 23. Field investigations conducted since 2004 indicate that illegal timber has entered China from globally distributed producer countries, including Lao PDR, Indonesia, Myanmar, Russian Federation, Mozambique and Madagascar, as well as coming from China itself28; Myanmar especially has been the subject of global scrutiny into the overland flow of illegal timber into China35,36,37. However, there is currently no legislation in place prohibiting the import of illegal timber products21, impeding the ability of Chinese law enforcement to take action on shipments of suspected illegal timber.

China’s role as the main global processor of timber into timber and paper products means that imports from China account for an increasing proportion of illegal imports into consumer countries, with highly processed products (such as furniture) more likely to contain illegally-sourced timber23. Between 2005 and 2015, more than 2 million m3 of RWE of potentially illegal timber is estimated to have entered into the EU from China in the form of EUTR and non-EUTR products33.

In 2013, imports from the Russian Federation (logs and sawnwood) and Indonesia (sawnwood and wood pulp) were indicated to be the two main sources of China’s timber and paper imports with high risk of illegality23. However, since 2013, Indonesia has exported timber to China with Indonesian Verified Legal (V-legal) licence documents, which constitute a proof of legality under Indonesian law38, and on 15 November 2016, Indonesia began issuing FLEGT licences to verify legality of timber exported to the EU39. From the Russian Federation, volumes of Mongolian oak logged for export to China exceeded the authorised logging volumes 2004-2011 by two to four times40; China also imports over 95% of the valuable hardwoods exported from the Russian Far East, where 50-80% of precious hardwood cut is estimated to have been harvested illegally, according to a report by the EIA41. Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands are also becoming increasingly important sources of likely illegal timber products due to their increased volume of timber-based exports21,23,28. Papua New Guinea was the fourth largest source of rough wood (HS 4403) imports to China in 2015 by weight19; links have been made between illegally granted Special Agriculture and Business Leases in Papua New Guinea and import of logs harvested from land with such leases into China42. A 2018 report on illegal logging in Papua New Guinea cautioned that imports of ‘high risk’ timber from PNG could damage China’s trade relations with EU and US buyers of Chinese timber products43. Timber stocks in the Solomon Islands have been severely over-harvested, with log export volume increasing rapidly 2002-201444. Corruption among logging companies and government officials in the Solomon Islands was reported to have contributed to excessive logging45,44.

Import of logs has also been reported from countries with a log export ban (LEB), including Equatorial Guinea, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire21; this was also seen for Indonesia (which enacted a log export ban in 2001), with Chinese reported imports of Indonesian logs post Indonesia’s LEB in 200119,21,28, which may be indicative of illegal trade. Although Nigeria has had an export ban on rough and sawn wood in place since 197629,46, a report by EIA found evidence of over 1.4 million “kosso” (Pterocarpus erinaceus) logs with an estimated value of USD 300 million being stopped by Chinese customs officials upon attempted entry to China in 201647. In 2017, Nigerian CITES authorities issued around 4000 retrospective permits, releasing the held logs47. EIA reported that the issuance of these permits was the result of a “grand corruption scheme” involving payments to senior Nigerian officials with alleged help from the Chinese consulate47. In 2018, Forest Trends reported that China had imported >46 million m3 of logs from 31 countries with either full or partial LEB 2005-2016, with many of these imports considered to be in violation of the bans48. Chinese log imports from LEB countries amounted to 20% of China’s total imports of logs 2005-2016, totalling USD 16 billion, with greatest values imported from Papua New Guinea, Lao PDR and Malaysia48.

Timber from rosewood (Dalbergia and Pterocarpus spp.) and ebony (Diospyros spp.) is in great demand in China for Hongmu furniture24,29, for example. Until the genera were listed in the CITES Appendices in June 2013 (Diospyros) and January 2017 (Dalbergia), 98% of exports from Madagascar of these genera were imported by China49. The rapid rise in demand for the timber species listed in the official Chinese National Hongmu Standard has been linked to increases in illegal logging in range states24 in Asia (especially countries bordering China such as Thailand, Cambodia and Lao PDR50), Africa (including Ghana, The Gambia, Senegal51) and Central and South America (including Guatemala25), as well as CITES compliance issues for CITES listed species52. In 2016, 15-20 major Chinese companies were reported as being actively involved in purchasing illegal precious timber from Madagascar25.

China’s timber products industry

China is a major importer of timber which is processed into timber and paper products in China for re-export; this industry is represented by a large number of processing factories (more than 100 000), many of them small and medium sized enterprises, where timber from multiple sources can be mixed, making traceability difficult32. The paper processing sector is dominated by five main companies: Nine Dragons, Shangdon Chenming, Lee & Man, Gold East Paper (APP) and Shandong Sun Paper, which together accounted for 18% of the market in 2008; Nine Dragons was the 21st largest global forest, paper and packaging industry company in 201553. The remainder of the paper producing industry consists of much smaller enterprises32. Smaller forest owners and suppliers may also transport and sell timber and timber products without the necessary licences (often transportation licences) due to the associated costs54; additionally, some timber products, such as pre-consumer recycled sawdust, wood chips and furniture waste, which are processed into further timber products, do not require transport licences54. Both of these factors hamper supply chain traceability.

China’s forestry management and legislation

Forest management is supposed to follow a five year plan set out by the State Forestry Administration32. Each Province or state farm is assigned a yearly operating quota, which is then distributed between each operating licence holder32. The Natural Forest Protection Program, which covers the conservation and regeneration of natural forests, is the legislation governing China’s current natural forest logging ban26. It is important to note that since this ban in 2017, availability of Chinese hardwood species, such as Mongolian oak, is likely to have reduced, as large scale plantations of the species have not yet matured55. Species mis-declaration may therefore become a potential issue. Plantations supply the majority of domestically consumed logs12. China has also introduced its own certification scheme for forests, the “China Forest Certification Scheme”, launched in 201032 and endorsed by PEFC in 201456.

The Chinese government published a draft timber legality verification scheme (TLVS) in 201121. Chinese timber industry associations have also now developed their own legality standards and frameworks57. As part of this, the China National Forest Products Industry Association (CNFPIA) developed a TLVS (released in September 2017), which is envisaged as an important element of the national China TLVS57. This standard sets out the requirements for legality at the forest management level and throughout the chain of custody and will apply to domestically harvested and imported timber57. Implementation of the standards and tools being developed as part of the TLVS is currently forseen as voluntary57, although the Chinese government is planning to put in place mandatory regulations which will require companies to demonstrate that their timber imports are legal57. The Chinese Academy of Forestry (CAF) is also supporting companies to establish due diligence systems based on a toolkit developed by the CAF57. CAF also launched a China Responsible Forest Product Trade and Investment Alliance (China-RFA), which is, inter alia, “working to establish partnership agreements with international market participants to support the capacity building of Chinese enterprises and to establish collaborative partnerships to promote responsible business”57.

Take-up of third party chain of custody certification (CoC) is also increasing, for example, over 5000 FSC CoC certificates and nearly 300 PEFC CoC certificates are currently held by Chinese organisations, 10,11.

China and the EU have established a Bilateral Coordination Mechanism (BCM) to facilitate cooperation to reduce illegal logging and the associated global trade in illegal timber, intended to act as a forum for policy dialogue and a mechanism for sharing information on policies and legal frameworks, as well as coordinating relevant initiatives6.

| RELEVANT LEGISLATION AND POLICY[1] | ||

| For further details on China’s legislation relevant to EUTR, see the China country page on FAOLEX and NEPCon (2017) ‘China list of applicable legislation’. | ||

| Forestry Law of the People’s Republic of China (1984, amended 1998 and 2009)

Forestry Act (1979) Measures for Administration of National Public Forests (2013, amended 2017) Regulations for the Implementation of the Forest Law (2000) Natural Forest Protection Program (2000) Environmental Protection Law (1989) Law on the Prevention and Control of Desertification (2001) Environmental Impact Assessment Law (2003) Land Administration Law (1998, amended 2004) Regulations for the Implementation of the Land Administration Law of China (1998) Constitution of the People’s Republic of China (as amended 2004) A Guide on Sustainable Overseas Forests Management and Utilization by Chinese Enterprises (2009) Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Administration of Import and Export of Endangered Wild Animals and Plants (2006) Foreign Trade Law of the People’s Republic of China (2004) Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on the Administration of Import and Export goods (2001) Measures for the administration of import licences for goods (2004) |

Code of practice for the issuing of import licences (2007)

Code of practice for the issuing of export licences (2007) Measures for the administration of small and medium border trade and border areas for foreign economic and technical cooperation (1996) Customs law of the People’s republic of China (1987) Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Implementing Customs Administrative Penalty (2004) Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Import and Export Duties (2003) Regulations on the Origin of Import and Export Goods of the People’s Republic of China (2004) Law of the People’s Republic of China on Import and Export Commodity Inspection (1989) Regulations for the Implementation of the Law of the People’s Republic of China concerning Import and Export Commodity Inspection (2005) Law of the People’s Republic of China on Entry and Exit Animal and Plant Quarantine (1992) Regulations for the Implementation of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Entry and Exit Animal and Plant Quarantine (1996) The measures for the administration of the quarantine of the articles carried by persons on entry or exit (2002) Log import quarantine requirements (2001) |

|

| LEGALLY REQUIRED DOCUMENTS[2] | ||

| See WWF GFTN ‘Guide to legal and responsible sourcing’ and NEPCon (2017) ‘China document guide’ for a further list and examples of legally required documents. | ||

For harvesting:

For transporting:

For processing:

|

For export:

For export products made of timber originally imported into China from another country:

Quarantine certificate |

|

[1] The following list may not be exhaustive and is intended as a guide only on relevant legislation.

[2] The following list may not be exhaustive and is intended as a guide only on required documents.

*This overview does not consider Hong Kong SAR, Macao SAR or Taiwan (Province of China)

References

- FAO. FAO Country Profiles: China. (2018). Available at: http://www.fao.org/countryprofiles/index/en/?iso3=CHN. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015. Desk reference. (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2015).

- Rights and Resources Initiative. Tenure data tool. (2018). Available at: https://rightsandresources.org/en/work-impact/tenure-data-tool/#.WjjlOVVl9ph. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- UNEP-WCMC. Protected Area Profile for China from the World Database of Protected Areas. (2018). Available at: https://www.protectedplanet.net/country/CN. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- EU FLEGT Facility. VPA countries. (2018). Available at: http://www.euflegt.efi.int/vpa-countries. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- EU FLEGT Facility. EU-China cooperation. (2014). Available at: http://www.euflegt.efi.int/es/eu-china. (Accessed: 2nd June 2018)

- FAO. Contribution of the forestry sector to national economies, 1990-2011, by A. Lebedys and Y. Li. Forest Finance Working Paper FSFM/ACC/09 (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, 2014).

- United Nations Statistics Division. UN Comtrade Database. (2018). Available at: https://comtrade.un.org/data/. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015: How are the world’s forests changing? (Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, 2016).

- FSC. Facts and figures August 2018. (Forest Stewardship Council, 2018).

- PEFC. PEFC Global Certification: Forest Management & Chain of Custody. (2017). Available at: https://www.pefc.org/resources/webinar/747-pefc-global-certification-forest-management-chain-of-custody. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- European Timber Trade Federation. China Industry Profile. Gateway to International Timber Trade (2018). Available at: http://www.timbertradeportal.com/countries/china. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- UNEP-WCMC. The Species+ Website. Nairobi, Kenya. Compiled by UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge, UK. (2018). Available at: https://speciesplus.net/. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- World Justice Project. Rule of Law Index 2017-2018. (2018). Available at: http://data.worldjusticeproject.org/. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- Transparency International. Corruption Perceptions Index 2017. (2018). Available at: https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2017. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- Fund for Peace. Fragile States Index 2018. (2018). Available at: http://fundforpeace.org/fsi/. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- Freedom House. Freedom in the World. (2018). Available at: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world-2018-table-country-scores. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- European Commission. Eurostat. (2018). Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database. (Accessed: 2nd July 2018)

- United Nations Statistics Division. UNCOMTRADE database. (2017). Available at: https://comtrade.un.org/data/.

- IUFRO. Illegal logging and related timber trade – dimensions, drivers, impacts and responses. A global scientific rapid response assessment report. (IUFRO World Series Volume 35, 2016).

- Wellesley, L. Trade in illegal timber: the response in China. (Chatham House, 2014).

- The World Bank. Bribery incidence (% of firms experiencing at least one bribe payment request). (2017). Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IC.FRM.BRIB.ZS.

- Hoare, A. Tackling illegal logging and the related trade: what progress and where next? (Chatham House, 2015).

- EIA. The Hongmu Challenge: A briefing for the 66th meeting of the CITES Standing Committee, January 2016. (EIA, 2016).

- EIA. CoP17 Inf. 79. Analysis of the demand-driven trade in Hongmu timber species: impacts of unsustainability and illegality in source regions. (EIA, 2016).

- Kram, M. et al. Protecting China’s biodiversity: a guide to land use, land tenure, and land protection tools. (The Nature Conservancy, 2012).

- Nellemann, C. & INTERPOL Environmental Crime Programme. Green carbon, black trade: illegal logging, tax fraud and laundering in the world’s tropical forests. (UNEP/GRID-Arendal, 2012).

- EIA. Appetite for destruction: China’s trade in illegal timber. (EIA, 2012).

- Forest Legality Initiative. Logging and export bans. (2017). Available at: http://www.forestlegality.org/content/logging-and-export-bans. (Accessed: 26th April 2017)

- European Commission. European Union Restrictive measures (sanctions) in force. (European Commission, 2017).

- United Nations Security Council. Consolidated United Nations Security Council Sanctions List 27 November 2017. (United Nations Security Council, 2017).

- Xiufang, S. & Canby, K. China: Overview of Forest Governance , Markets and Trade. (Forest Trends for FLEGT Asia Regional Programme, 2010).

- Sepul, B., Penttilä, J. & Malmström, M. China as a timber consumer and processing country: an analysis of China’s import and export statistics with in-depth focus on trade with the EU. (INDUFOR and WWF-UK, 2016).

- Brack, D. Chinese overseas investment in forestry and industries with high impact on forests: official guidelines and credit policies for Chinese enterprises operating and investing abroad. (Forest Trends, 2014).

- Global Witness. A disharmonious trade: China and the continued destruction of Burma’s northern frontier forests. (Global Witness, 2009).

- EIA. Organised Chaos: The illicit overland timber trade between Myanmar and China. (EIA, 2015).

- Forest Trends. Analysis of the China-Myanmar Timber Trade. (Forest Trends, 2014).

- FLEGT. V-legal documents. FLEGT (2017). Available at: http://www.flegtlicence.org/v-legal-documents.

- EU FLEGT Facility. Indonesia: all about the Indonesia-EU Voluntary Partnership Agreement. (2018). Available at: http://www.euflegt.efi.int/indonesia. (Accessed: 28th June 2018)

- Smirnov (ed.), D. Y., Kabanets, A. G., Milakovsky, B. J., Lepeshkin, E. A. & Sychikov, D. V. Illegal logging in the Russian Far East: global demand and taiga destruction. (WWF Russia, 2013).

- EIA. Liquidating the forests: hardwood flooring, organised crime and the World’s last Siberian tigers. (EIA, 2013).

- Global Witness. Stained trade: How U.S. imports of exotic flooring from China risk driving the theft of indigenous land and deforestation in Papua New Guinea. (Global Witness, 2017).

- Global Witness. A major liability: illegal logging in Papua New Guinea threatens China’s timber sector and global reputation. (Global Witness, 2018).

- Katovai, E., Edwards, W. & Laurance, W. F. Dynamics of logging in Solomon Islands: the need for restoration and conservation alternatives. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 8, 718–731 (2015).

- Kabutaulaka, T. T. in Culture and Sustainable Development in the Pacific 33 (ed. Hooper, A.) 88–97 (Culture and Sustainable Development in the Pacific, 2005).

- Federal Ministry of Finance. Export prohibition list. Federal Government of Nigeria (2018). Available at: https://www.customs.gov.ng/ProhibitionList/export.php. (Accessed: 18th January 2018)

- EIA. The rosewood racket: China’s billion dollar illegal timber trade and the devastation of Nigeria’s forests. (EIA, 2017).

- Schaap, B. & Canby, K. China’s log imports from countries with log export bans: trade trends and due diligence risks. Forest Trends Policy Brief. (Forest Trends, 2018).

- Ke, Z. & Zhi, Z. The trade of Malagasy rosewood and ebony in China. TRAFFIC Bull. 29, 22–32 (2017).

- EIA. Routes of Extinction: The corruption and violence destroying Siamese rosewood in the Mekong. (EIA, 2014).

- Treanor, N. B. China’s Hongmu consumption boom: analysis of the Chinese rosewood trade and links to illegal activity in tropical forested countries. (Forest Trends, 2015).

- EIA. Prohibited permits: ongoing illegitimate and illegal trade in CITES-listed rosewoods in Asia. (EIA, 2017).

- PwC. Global forest, paper and packaging industry survey: 2016 edition survey of 2015 results. (PwC, 2016).

- Grant, A. & Beckham, S. IKEA’s response to the Lacey Act: due care systems for composite materials in China. (World Resources Institute, 2013).

- Forest Trends. China’s Logging Ban in natural forests: Impacts of extended policy at home and abroad. (Forest Trends, 2016).

- PEFC. China’s National Forest Certification Scheme acheives PEFC endorsement. (2014). Available at: http://pefc.org/news-a-media/general-sfm-news/1459-china-s-national-forest-certification-system-achieves-pefc-endorsement. (Accessed: 23rd May 2017)

- EU FLEGT Facility. Introduction to China’s Timber Legality Verification System. (2017).